Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi is a German mathematician who was born in

the early 19th century. He has a reputation as one of the finest

mathematicians the world has ever known. But just why would a math

wizard appear in an investing article here?

Thing is, Jacobi has a phrase that’s oft-quoted by investing maestro

Charlie Munger and that is, “Invert, always invert.” Jacobi believed

that problems are best solved when inverted. I believe this applies to

investing too.

So, instead of asking “What should I do to make money in stocks,” a better question could be “How should I avoid losing money when investing?”

To answer the latter question, below are three things we can do.

While the list I have here is not exhaustive as a ‘how-to’ on minimising

your odds of losing money while investing, it’s still a good place to

start.

1. Avoid short-term stock market forecasts

It’s tempting to listen to the views of highly-paid and

well-respected finance professionals on the stock market’s short-term

future and then invest accordingly. But, it’s worth noting how horrible

their collective track-records are.

Financial institutions (think banks and investment firms) on Wall

Street, the Capital of finance in the U.S., have people who work as

“market strategists.” These guys (and gals) are well-read, highly

educated, very well-compensated – and very wrong at times.

One of their key jobs involves forecasting, at the start of the year, where the S&P 500 (one of the key stock market indexes in the U.S.) will be by the end of it. Earlier this year, my colleague Morgan Housel had looked at these strategists’ track records going back to 2000. He then plotted the results of each year’s average forecast into the chart seen below:

Source: Birinyi Associates, S&P Capital IQ (Morgan Housel)

The chart shows that the forecasts were wildly different from the

market’s actual performance in many of those years (the blue bars

represent the average forecast gain while the red bars represent the

market’s actual return). In fact, according to Morgan, “the strategists’ forecasts were off by an average of 14.7 percentage points per year.”

2. Be careful with highly-valued shares

Shares with expensive-looking valuation metrics are not always bad

investments. But, it pays to at least be careful with a stock that is

very highly-valued.

Near the end of May this year, Jason Holdings Limited (SGX: 5I3), a company that provides timber flooring services, was trading at S$0.64 and being valued at 330 times its trailing earnings and 9.4 times its book value.

At that time, the market – as represented by the SPDR STI ETF (SGX: ES3), an exchange-traded fund which tracks the fundamentals of the market barometer, the Straits Times Index (SGX: ^STI) – had a price-to-earnings (PE) ratio of just 14.

Today, Jason Holdings’ shares are exchanging hands at S$0.073 each, some 88% lower than the price of S$0.64.

3. Pay close attention to companies with high-debt

Debt can be used in a smart manner by companies to create value for

shareholders. But, debt can also be a source of big trouble, especially

when companies start piling it on.

The late Walter Schloss, who is an investor with a great long-term track record,

once wisely said: “I don’t like debt because it can really get a

company into trouble.” It’s such a simple yet powerful statement.

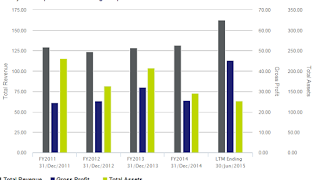

Fishmeal producer China Fishery Group Ltd (SGX: B0Z)

is a vivid example of the potential destructiveness of debt. As you can

see in the chart below, the company has been heavily-leveraged (as

alluded to by the high net-debt position) for many years:

Source: S&P Capital IQ

Last week, Bloomberg revealed

that one of China Fishery’s lenders, the bank HSBC, had taken legal

action against the company because of debt-related issues. China Fishery

has since appointed provisional liquidators to help deal with the

problem and suspended the trading of its shares. The company’s stock has

fallen by 73% over the past year.

1:30 PM

1:30 PM

Unknown

Unknown